The Referendum was an instruction to make an omelette. Eggs were cracked. More will be. And scrambled. And when they are, they are.

Since the result became known I’ve written twice: this on how we might avoid leaving the EU and this on whether the decision to leave is one for our elected Parliament or an unelected Prime Minister. Those posts have been widely read. I have been asked by different groups to help them think through what happens next.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, much of their thinking – and some of my own – has focused on whether the electorate’s decision to Leave might be reversed. I have, since Friday, said that I think it between very possible and probable that, in some form or other, we will not Leave. That remains my view. But in working to achieve that goal it is important to keep ahold of what it is that we really seek.

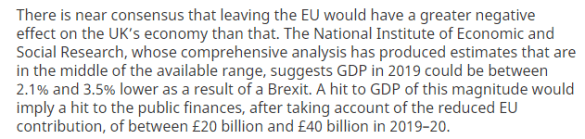

The City is concerned about the impact of Leaving upon its health. The thoughtful among us should be concerned about that concern. Although many of us would agree that the City should not be so important to the public finances of the United Kingdom, still it is important. Reducing our exposure by generating other strengths is a gradual exercise which, properly conducted, would take decades. To reduce it by Leaving is like losing weight by severing a leg. And alongside the economic impact of Leaving on the City – and at least as important – will be the impact on the so-called ‘real’ economy.

Some worry about what Leaving means for an apparently – the data is unclear – growing class of people living economically marginal lives. On all objective analyses, Leaving will generate meaningful pain for those least well-placed to bear it. I’ve written elsewhere about what shape that pain takes. I shan’t repeat it here.

Others are concerned about what Leaving means for our cultural fabric. I spoke earlier this week to a Government minister who compared the campaign fought by members of the Leave team – and the subsequent upsurge in racial violence – to the ascension of Hitler in Nazi Germany. Some will say this is scare-mongering – but for others it is a profound worry.

Still others fear for the future of our democracy. What will happen when the truth about what Leaving means is revealed to those who were persuaded to vote for it?

There will be other concerns too. But in thinking about how to address them they must be separated out because they are different. And although their solutions overlap they are different too. And, and this is important to grasp, some eggs are scrambled already.

A reversal of the decision to Leave the EU might suture back on the leg. Not as good as it was – true – but much less bad than it could come to be. We might then ask seriously – not merely rhetorically as so often we hitherto have – what an industrial policy that generated growth in the real economy looked like.

A reversal should also help those living economically marginal lives. But the experience of many since the global financial crisis of 2008 is that there is a big difference between that “should” and “will.” Remaining might create the conditions within which more can be done. But Remaining won’t do it.

And if this is your concern your focus should be, alongside working to Remain, supporting those politicians whose commitment to the lives of working people is otherwise than synthetic. I am, for the moment, a member of the Labour Party so let me say this very clearly. Those politicians are to be found in all political parties: Labour is far from having a monopoly on morality or concern for the dispossessed. But the key point is this: even were we to step back from the precipice, Remaining will not automatically improve things for the poor.

As to the effects on the cultural fabric of our nation, this, egg is, I am afraid, already broken. Already, as Paul Lewis observed, the small minority of our country that is racist believes itself to have the express or tacit support of 52%. No doubt this was not the intention of those like Michael Gove who say, now, that they “shuddered” at the rhetoric of hate employed by their allies but said, then, nothing in case to do so cost a few votes. But even if the enormous upsurge in racial hatred was not Gove’s intention it was a predictable consequence and one he did nothing to stem. For him, it was a price worth paying to achieve the result he wanted. If you value our tolerance, you should oppose those prepared to sacrifice it to win a few votes.

Alongside opposing such politicians you should support the major public voices for pluralism in our society. You may find it hard to give money to the Guardian – there are personal reasons why it is extremely difficult for me – but without it a powerful, and positive, voice for tolerance is lost. Support it.

If you believe that fascism thrives when people feel ignored by ‘normal’ politics then the prospect of failing to deliver the result of the Referendum will rightly concern you. But lies were told about immigration and the NHS and jobs and public finances, and the lies will be discovered. Do we, do our politicians, wait until the victims discover that we knew of the lies all along and did nothing to tell them – do we kick the can down the road? Or do we confront the truth now for an environment where the underlying issues can better be addressed? The fight against what looked to that Government minister like fascism is only beginning. It is no time to opt for easy choices.

The concerns you may have about Leaving? Do not think that Remaining solves them. It is a necessary precondition. It is necessary but not sufficient.

Follow @jolyonmaugham

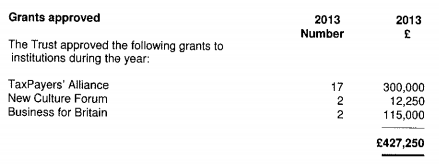

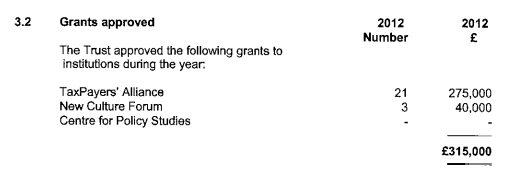

And 31 December 2012?

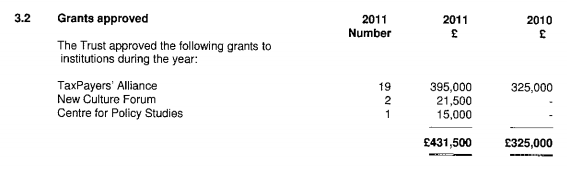

And 31 December 2012? And 31 December 2011 and 2010?

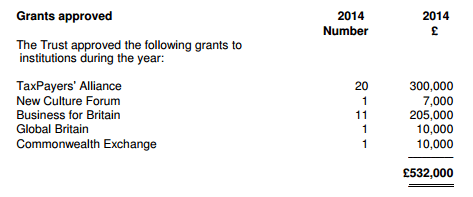

And 31 December 2011 and 2010? So over those five years PERT made 95 grants (including

So over those five years PERT made 95 grants (including

You must be logged in to post a comment.