Yesterday Zac Goldsmith issued a Press Release with some details of his tax returns for the past five tax years. I’ve set it out below for those who haven’t seen it. But what do we know about his tax affairs? And what can we learn from the Press Release?

He inherited non-dom status from his father, Sir James Goldsmith. And it is a matter of public record that he benefits from an offshore trust (the “Trust”) established by Sir James to provide Zac and his siblings with an income. Some estimates suggest the Trust has a value of around £300m.

Zac says he relinquished non-dom status with effect from the tax year 2009-10. We don’t know when this happened – but it is likely to have taken place after May 2006 when he was placed onto the so-called A List for the selection of Conservative Party candidates. The decision may have been precipitated by his expectation of his finances becoming a matter of greater public interest. It may also have been affected by changes to the non-dom regime with effect from 2009-10 that rendered it less attractive. In any event in 2010 Parliament enacted the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act which deemed MPs and members of the House of Lords (although not Mayors) to be UK domiciled for income tax, capital gains tax and inheritance tax purposes.

The Tax Consequences

To understand what all of this means in tax terms, it’s best to divide the income and gains made by the Trust into three categories:

(1) those that the trustees who run the trust appoint to Zac and he doesn’t bring into the United Kingdom;

(2) those that the trustees who run the trust appoint to Zac and he does bring into the United Kingdom; and

(3) those that the trustees who run the trust don’t appoint to Zac at all.

The Trustees are likely to have only a minimal liability to tax on these three categories. But what about Zac?

Before Zac became UK domiciled, type (1) income and gains would have escaped liability to UK tax whereas a UK dom would have paid tax on them. Zac hasn’t disclosed his tax records from the period for which he was a non-dom – but even if he did we wouldn’t learn much. Type (1) income and gains wouldn’t appear on his UK tax returns.

But now that he is a UK domiciliary, type (1) income and gains, along with those in type (2), will be subject to UK tax. And we can see from the letter below that he has received between £53,000 and £2.2m per annum from the trust and paid appropriate amounts of tax.

But the interesting category is type (3).

It is highly likely – although I could not say that I know this – that the Trust is a discretionary trust. What that means is that the trustees can choose whether and when to ‘appoint’ income and gains to Zac – and they are likely to have regard (amongst other things) to what is convenient to Zac. Should it be convenient for him to receive income and gains later, the money he might otherwise have taken now will continue to sit abroad, largely or wholly untaxed, and roll up tax free until such time as – perhaps – Zac ceases to be UK resident when the money could be received by him free of UK (or perhaps any) tax.

Indeed, the Trustees taking Zac’s wishes and needs into account is the most likely explanation for the bumpy profile of his receipts from the trust.

It should also be noted that, broadly to such extent as the property in the Trust is not based in the UK, it will escape liability to UK inheritance tax. Ordinarily a discretionary trust is subject to a charge of up to 6% every ten years – but this is not so for a trust established by a non-dom.

What should we make of this?

Let’s assume Zac is leaving money in the Trust until he needs it – which on the basis of very limited information available is possible or probable – is this aggressive tax planning?

I think not.

It wasn’t Zac who set up the Trust. Responsibility for the fact that, in consequence of it being offshore, the Trust does not generate a liability to UK tax on (most) income and and gains cannot be laid at his door. And the same is true of the fact that the arrangements avoid an inheritance tax liability.

And few would argue that any of us have a positive obligation to maximise the tax we pay. Drawing down money as we need it, and remaining mindful of the tax consequences of doing so, is the sort of decision all of us with pensions are now going to have to make.

Some will think that it is enough that he is receiving very substantial amounts of unearned money. For myself I’d rather judge him on the quality of his policies.

But that’s not a technical question – and it’s one on which we can all form our own view.

What, on any view, Zac should be applauded for is the decision to provide a degree of voluntary disclosure of his tax affairs. But better still would be disclosure of his actual tax returns – rather than merely extracts from them.

Now let’s see what Sadiq Khan provides.

Zac delivers on tax transparency commitment

Zac Goldsmith has today published the details of his tax payments, delivering on the commitment he made to do so last week.

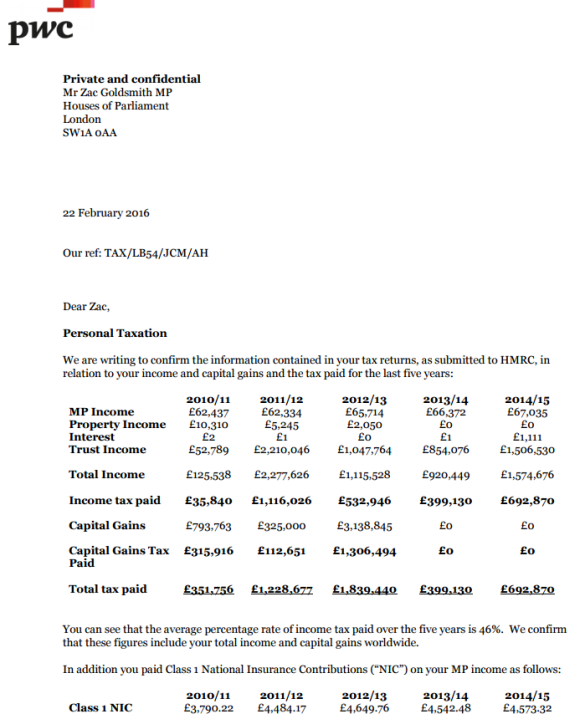

A letter from Zac’s accountant, prepared at his request, confirms the details of his worldwide income, capital gains, and tax payments in each of the years since he first held public office.

Zac Goldsmith said:

‘I have today published my tax return details, prepared and verified by PwC, who have represented me all my adult life.

‘I gave a commitment to do so and today I deliver on that promise. I look forward to all mayoral candidates doing the same so London voters can judge us equally.

‘As was well known to voters in my two elections as an MP, I became ‘non-dom’ automatically because of my father’s international status. It was not a choice, and I relinquished it seven years ago. I was born, grew up and have always lived in London – except for two years travelling abroad in my early 20s. Because of this I derived very little, if any, benefit from this status as my income came to the U.K and was therefore taxed here.

‘It is no secret I was dealt a good hand in life, but I have been determined to play it well. I have stood up for my local community in Parliament for six years, delivering on my promises to them – which is why they returned me with one of the biggest increased majorities at the last election. I am proud of my record and I will stand up and deliver for all of greater London, just like I have for Richmond, should I be elected mayor in May.’

ENDS

And the attached letter provides as follows:

You must be logged in to post a comment.