This should shock you – but it won’t.

- The DUP’s Treasurer, Gregory Campbell, gave an on-the-record interview to SourceMaterial. That interview was recorded and, assuming he told the truth, the shadowy Constitutional Research Council, which gave £435,000 to the DUP, looks to have broken the law

- If Mr Campbell was telling the truth, both he and the DUP are also likely to have broken the law.

- You might hope but you can no longer expect that the Electoral Commission would conduct a proper investigation into these facts but – as will be seen – its investigation was at best cursory.

- And it may well have misled the public in its statements about those investigations.

Four striking assertions. Made all the more striking when you bear in mind that, according to the BBC, £435,000 is the “biggest known political donation in history for a Northern Ireland party.” Below I try and stand them up, mostly by reference to documents that I am able to publish. But occasionally by reference to other materials I can vouch for.

But first let me explain that we are concerned with two sets of rules. The first is about transparency – the general rule that we should know who is buying democratic influence. This is the rule that I believe the CRC infringes against. The second is about who is allowed to buy democratic influence – and this is the rule that I believe the DUP infringes against.

Has the Constitutional Research Council broken the law?

The DUP, a Northern Irish political party, received a donation of £435,000 from the CRC and went on to spend £282,000 of that sum advertising in London’s Metro, outside of Northern Ireland.

Following the Good Law Project’s success on Friday in its High Court action against the Electoral Commission we know that if a donor (here the CRC) controls the use to which a donee (here the DUP) spends money that donor will incur referendum expenses which will go towards its spending limit.

Here is how the High Court put the matter (para 81):

“If… money (i) is paid directly by the donor (by agreement with the donee) to discharge a liability of the donee to pay for goods or services falling within Part I of Schedule 13 of PPERA or (ii) is paid pursuant to an agreement to pay or reimburse the donee for the cost of such goods or services purchased by the donee, or (iii) is given on terms (binding on the donee) that it is to be used to purchase or pay for particular qualifying goods or services, then the expenses incurred in making such a “specific” donation are appropriately regarded as incurred “in respect of” a matter falling within Part I of Schedule 13 of PPERA and hence as “referendum expenses”.”

This is little more than common sense, really, because otherwise you could avoid the transparency limits by channeling your expenditure through someone else.

The Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 says that you cannot incur referendum expenses of more than £10,000 unless you are a permitted participant. To be a permitted participant you have to register. The CRC did not register.

So the missing link is whether the CRC controlled the use to which the DUP put the donation. If it did the CRC will have broken the law. Did it? The answer to that question seems abundantly clear.

First, why would the DUP want to spend £282,000 on a Metro advertisement in London. Why would a Northern Ireland political party do that? Instead of spending it on its own concerns in Northern Ireland? Would the DUP really have spent that amount of money on an advertisement in England had it not been obliged to do so? For scale, £282,000 is more than twice the DUP’s declared party level spending in the last three general elections combined.

Second, the BBC Spotlight programme asserts that Richard Cook, the Scottish Chair of the CRC and not involved the DUP, booked the advertisement on which the DUP claims to have spent £282,000. I understand it was not contradicted either by the DUP or Richard Cook. This is strongly supportive of the notion that the CRC controlled the use to which the ‘donation’ was put.

And, third, in an on-the-record recording of the SourceMaterial interview, the DUP’s Treasurer himself says that the CRC controlled the use.

“For example the Metro money, it’s very straight forward, we got an amount of money to use as an advert in the referendum campaign, we used it to the purpose it was given and accounted for it after we had spent it. Nothing hidden about that. The advert had said who had put the advert on, i.e. the Democratic Unionist party and we declared it within the time scale we were required to do so afterwards. So there is nothing secretive about it.”

If the DUP’s Treasurer was telling the truth it is hard to escape the conclusion that the CRC has broken the law by failing to register as a permitted participant.

There are a number of reasons why this matters.

By enacting the legislation Parliament was saying it is important that we know who is buying influence in our democracy. The sum of money spent on the Metro ad was a very substantial one. And the sum was spent in a very unusual way – channeling expenditure on an advertisement in England by an organisation with links to the Scottish Conservative Party through a Northern Ireland political party – presumably to take advantage of strict secrecy laws that enable a donor to a Northern Ireland party to escape public scrutiny.

It is impossible to imagine that this was what Parliament intended the law should permit – that donations connected with spending in England should escape public scrutiny. If the CRC had placed the Metro ad directly it would have had to register as a participant and disclose its donors. Should it really be able to escape that obligation by funneling it through the DUP? In the circumstances, there really ought to be very close scrutiny of whether an apparent attempt to squeeze through a technical loophole to achieve a counter-purposive result – a ruse – succeeded. As I have set out, I think it reasonably clear that it did not.

And has the DUP broken the law?

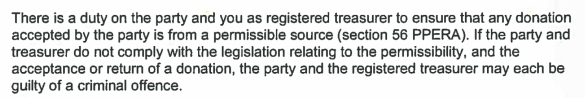

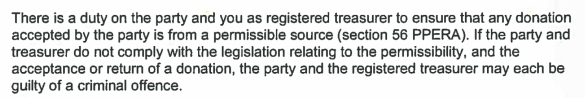

Broadly speaking, section 54 of the Act imposes a requirement on those receiving donations to check that the donor is a “permissible” donor. And section 56 of that Act makes it a criminal offence to keep a donation where you do not know whether the donor is a permissible donor. Here is how the Electoral Commission characterised the DUP’s duty – in a letter to the DUP.

Did the DUP carry out that duty?

Here is what the DUP’s Treasurer, Gregory Campbell, told SourceMaterial in an on-the-record interview (I hold a copy of the recording).

“Q. The organisation was the constitutional research council… so who are they, apart from your man that was in the papers

“A Presumably they are right of centre pro leave the EU [my emphasis].”

He is asked:

“Q. Had you heard of the CRC before they came.

“A. I haven’t heard of it before and I haven’t heard of it since. It doesn’t make any difference. The important people are the Electoral Commission… And who are the people whose duty it is to monitor and regulate these things? The Electoral Commission. It’s their verdict that counts. Not what you think, or what I think, or what somebody else thinks [my emphasis].”

And he says (48m)

“How would I or anybody in our party be expected to know who the individuals are that are involved in the organisation? Why would it be my business to find out?”

And he says (45m)

“If the Electoral Commission had come back said there is something I’ve missed here, I would say ‘Right guys, where did this money come from?’ or ‘Who gave it to you?’.”

But section 56 of the Act imposes a mandatory obligation on the DUP to verify the identity of the donor and check whether it is a permissible donor. And, looking at the comments made by the DUP’s Treasurer, and taking them to be the truth, it is hard to see how that obligation was carried out.

So why does this matter?

Parliament has seen fit to legislate to prevent foreign interference in our democracy. It does this by placing responsibilities on donees to check that donations they receive are from permissible sources – and those responsibilities are backed by the criminal law. This was a very substantial donation – apparently the largest in Northern Irish history. And, unless its Treasurer was lying, the DUP seems completely to have ignored the responsibilities placed on it by Parliament.

What investigation did the Electoral Commission carry out into the DUP’s acceptance of the donation?

Very shortly after the broadcast of the BBC Spotlight programme that revealed that Richard Cook had booked the Metro ad the Electoral Commission wrote to the BBC asking it to provide all information relevant to breaches of the Act.

On 17 July 2018 the BBC replied and, I understand, set out amongst other materials the exchanges with the DUP’s Treasurer contained above. I understand that the Electoral Commission did not ask the BBC – or SourceMaterial – for a copy of the recording on which that segment of the programme was based.

And, from the correspondence, it looks as though the Electoral Commission had decided not to investigate whether the DUP had broken the law even before it received the BBC’s response. We know from the Electoral Commission’s reply to the BBC that the BBC responded on 17 July 2018. But it was several weeks earlier, on 27 June 2018 the day after the Spotlight was broadcast, that the Electoral Commission wrote to the DUP. And it didn’t ask the DUP about the recording – or about what due diligence the DUP had undertaken. It didn’t even pretend to consider opening an investigation. It simply said that the comments were a “sufficient cause of concern for me to write to remind you or you (sic.) legal obligations.”

If you read the final paragraph of that letter it is abundantly clear that the letter was written to aid the DUP’s understanding. The Electoral Commission was not contemplating an enquiry into whether, as the DUP’s Treasurer had suggested, the Party had ignored its obligation to do due diligence in relation to the largest known political donation in Northern Irish history.

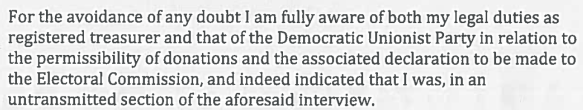

And the Electoral received this unapologetic response from the DUP which asserted that what was broadcast was used “out of context” and “in an attempt to convey an incorrect impression” and went on to say:

But, again, the Electoral Commission did not ask the BBC or SourceMaterial for a copy of the interview.

The Electoral Commission then replied to the BBC on 2 August 2018 saying:

“we reviewed the information you provided… Our conclusion is that we do not have grounds to open an investigation into the allegations about breaches of electoral law in the BBC NI Spotlight Programme.”

However, the sequence of events set out above suggests that the Electoral Commission did not review the information the BBC provided before concluded not to open an investigation. The evidence is that it never had any intention of considering an investigation, irrespective of what evidence the BBC provided. Because the Electoral Commission wrote to the DUP ‘reminding it of its obligations’ (and doing no more) before it was provided with the evidence it had requested from the BBC.

I do not find it easy to understand how the matters set out above under “Has the DUP broken the law?” do not give rise to grounds to open an investigation. But I find it very difficult indeed to understand how the Electoral Commission could apparently properly conclude, before reviewing the evidence it had requested, that an investigation into the DUP should not be opened.

Has the Electoral Commission made misleading statements?

How did the Electoral Commission present the exercise it carried out?

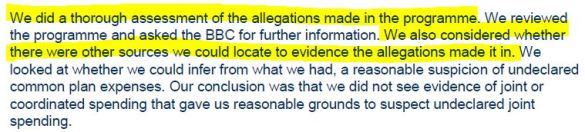

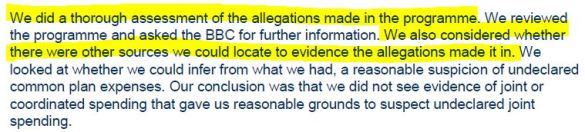

Here is what the Electoral Commission said to Ben Bradshaw MP:

What about the first of these highlighted sentences. Did the Electoral Commission carry out a “thorough assessment of the allegations made in the programme”? In relation to the question whether the DUP broke the law the evidence suggests that the Electoral Commission had already decided to take no action before receiving the evidence. As to whether the Electoral Commission “considered whether there were other sources we could locate to evidence the allegations made in it”, I have been told in writing by Source Material and the BBC that the Electoral Commission did not request the recording of the interview with the DUP’s Treasurer. And there is no suggestion that the Electoral Commission asked Metro’s publisher for a copy of the purchase order for the advertisement to see who booked the Metro ad or where the money came from to pay for it or whether the booking pre- or post-dated the date of the donation.

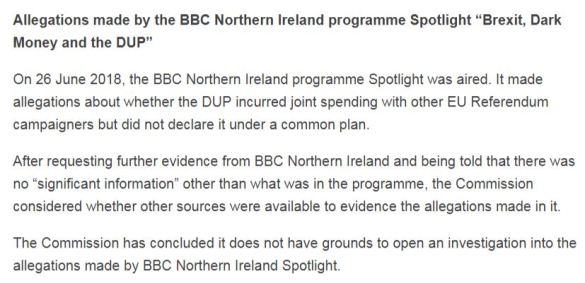

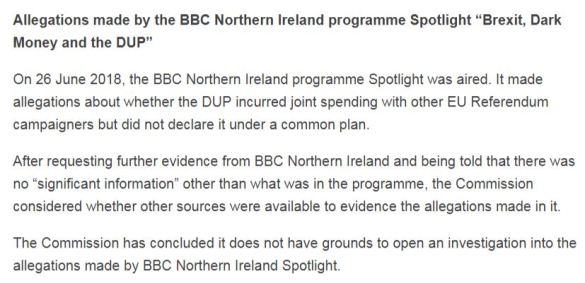

The Electoral Commission also made a similar statement to the public via this Press Release:

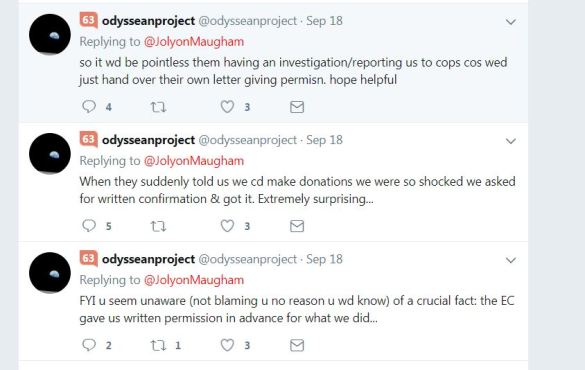

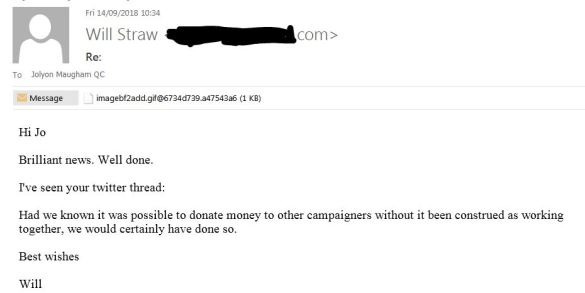

It is fair to say that the principal focus of this statement is on whether Vote Leave and the DUP were “working together”. But that issue was only one of the “allegations made in [Spotlight]”. Spotlight also asked the question set out above: “Did the DUP do enough homework into the financial background of their biggest donor?” (at 1.40 and then at 22.50) and broadcast certain of the extracts of the interview set out above under the heading above. And I understand that the Electoral Commission’s initial enquiry of the BBC was not confined to “working together” but asked for all information relevant to all PPERA offences. But, as I explain earlier, the Electoral Commission appears to have made the decision not to investigate the DUP before receiving any of the BBC’s evidence.

In the circumstances, it is hard to see how the Electoral Commission can properly suggest (see third sentence of the Press Release) that the decision not to investigate the DUP followed the BBC’s response.

***

These are very serious matters concerning what our national broadcaster has described as the “biggest known political donation in history for a Northern Ireland party”; they concern a Political party in a de facto Coalition Government; on their face they disclose law breaking and possible criminality; they appear (once again) to have been whitewashed by the Electoral Commission which appears to have closed its eyes to the evidence – and made statements to MPs and the public which are apt if not designed to mislead.

The Good Law Project – which I founded – is crowdfunding to take these matters to court again. Please, if you value our democracy, donate here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.