“Steve Thorburn trades as a greengrocer in Sunderland. In the course of his trade he used weighing machines calibrated in pounds and ounces. On 16 February 2000 he was warned by a properly authorised inspector that these machines did not comply with current legislation. He was served with a 28-day notice requiring that the machines be altered so as to yield measurements in metric units. He did not obey the notice. On 31 March 2000 the inspector obliterated the imperial measure stamps on his machines. He continued to use the now unstamped machines to sell loose fruit and vegetables by pound and ounce. He was prosecuted.” And then convicted.

So began Thorburn v Sunderland City Council [2003] QB 151 which you can read in full here. Whether Mr Thorburn was rightly convicted depended upon the operation of the so-called ‘doctrine of implied repeal’. The doctrine, as stated by Lord Justice Laws (one of many exemplars of nominative determinism to be found in our legal system), is this:

The rule is that if Parliament has enacted successive statutes which on the true construction of each of them make irreducibly inconsistent provisions, the earlier statute is impliedly repealed by the later. The importance of the rule is, on the traditional view, that if it were otherwise the earlier Parliament might bind the later, and this would be repugnant to the principle of Parliamentary sovereignty.

The provision compelling metrification of weights and measures was said to be found in the European Communities Act 1972 (the “ECA”). In a nutshell, Mr Thorburn argued that it had been implied repealed by the Weights and Measures Act 1985 (the “1985 Act”). To the extent that the ECA required Mr Thorburn to use metric measures it had been impliedly repealed by the 1985 Act which permitted the continuing use of imperial measures. The 1985 Act was inconsistent with the 1972 Act and so, he argued, had impliedly repealed it.

He relied upon what Lord Justice Maugham had stated (in a 1934 case):

The Legislature cannot, according to our constitution, bind itself as to the form of subsequent legislation, and it is impossible for Parliament to enact that in a subsequent statute dealing with the same subject-matter there can be no implied repeal. If in a subsequent Act Parliament chooses to make it plain that the earlier statute is being to some extent repealed, effect must be given to that intention just because it is the will of the Legislature.

Giving the only substantive judgment in the Divisional Court Lord Justice Laws held that, in fact, there was no inconsistency between the ECA and the 1972 Act. So one could not read the 1985 Act as impliedly repealing the ECA in any event. However, in case he was wrong, he went on to consider the extent of the doctrine of implied repeal.

He recognised that there were now certain types of legislative provision which cannot be repealed by mere implication. As he put it (at para 60):

The courts may say – have said – that there are certain circumstances in which the legislature may only enact what it desires to enact if it does so by express, or at any rate specific, provision.

Elaborating, he said (at para 62):

We should recognise a hierarchy of Acts of Parliament: as it were “ordinary” statutes and “constitutional” statutes. The two categories must be distinguished on a principled basis. In my opinion a constitutional statute is one which (a) conditions the legal relationship between citizen and State in some general, overarching manner, or (b) enlarges or diminishes the scope of what we would now regard as fundamental constitutional rights. (a) and (b) are of necessity closely related: it is difficult to think of an instance of (a) that is not also an instance of (b). The special status of constitutional statutes follows the special status of constitutional rights. Examples are the Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights 1689, the Act of Union, the Reform Acts which distributed and enlarged the franchise, the [Human Rights Act], the Scotland Act 1998 and the Government of Wales Act 1998.

Ordinary statutes may be impliedly repealed. Constitutional statutes may not be. For the repeal of a provision in a constitutional statute:

the court would apply this test: is it shown that the legislature’s actual – not imputed, constructive or presumed – intention was to effect the repeal or abrogation? I think the test could only be met by express words in the later statute, or by words so specific that the inference of an actual determination to effect the result contended for was irresistible.

So Mr Thorburn’s conviction stood. And the House of Lords refused him permission to appeal.

***

That’s legal history for you. I made it as interesting as I could.

The relevance of it all lies, of course, in the Conservative Party’s pledge this morning. Should they be re-elected they would introduce a new Act – call it the Tax Lock Act – which would bind the Government not to raise taxes. I have written about the pledge in more detail here.

But what is the substantive legal content of the pledge? That, of course, depends on the binding quality of the Tax Lock Act. If Parliament enacted it on Day 1 (pledging not to raise, say, VAT from 20%) and then introduced a Finance Bill on Day 2 (which raised VAT to 25%), what would the pledge do?

The short answer, clear beyond serious doubt, is absolutely nothing.

(1) I do not consider that a Tax Lock Act would be an Act – like Magna Carta or the Bill of Rights – which “conditioned the legal relationship between citizen and State in some general, overarching manner.” It follows that I consider it could be impliedly repealed.

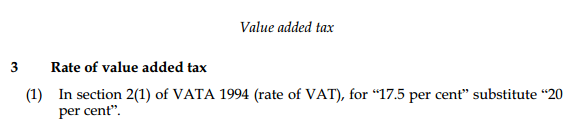

(2) If I’m wrong about (1) it seems to me that the hypothetical provision in the Day 2 Finance Bill raising VAT would give rise to an irresistible inference that Parliament intended to repeal the Day 1 Tax Lock Act (at least insofar as it said there would be no rise in VAT). You can best see why I might say this if you have regard to a recent provision whereby Government has raised a tax rate. Take, for example, this provision from the Finance (No 2) Act 2010:

It’s not easy to see how anyone could read this otherwise than as intending to introduce the rate of VAT from 17.5% to 20%.

(3) But even if I’m wrong about both (1) and (2), it is worth remembering that any future Conservative Government could simply choose explicitly to repeal the Tax Lock Act. Such is made abundantly clear in paragraph 59 of Lord Justice Laws’ judgment in Thorburn.

So, however you slice and dice the matter, it is abundantly clear that so far as legal content goes – I leave its political content to others – the pledge has none.

There are a number of these acts around, and they are simply political traps for the opposition, nothing more. It’s about the Tories daring the other parties to vote against the act, which they can then spin as ‘proof’ the other parties being in favour of tax rises.

It’s all very tiresome and a complete waste of everyone’s time.

Agreed, from a legal standpoint, the proposed Act would be virtually meaningless. Any weight that it carries is purely political.

Osborne was right the first time around, when he said that such legislation betrays a fear that either the Chancellor might lose his resolve, or that others might not believe him.

Lest anyone think this is a new phenomenon, or a specifically Conservative one, a reminder of this from Labour’s 2001 manifesto: “We will not introduce ‘top-up’ fees and have legislated to prevent them.” You might think that a party led by a lawyer would have known better (or perhaps they did). In any event, Labour proved the worthlessness of that supposed ‘lock’ by subsequently introducing top-up tuition fees…

Do you happen to recall whether Labour did, in fact, legislate to prevent them?

On a bit of investigation, I think the provision being referred to was s 26(3)-(4) Teaching and Higher Education Act 1998. This allowed the Secretary of State to require grants made by the Higher Education Funding Council to universities to be made under the condition that the universities charged specified amounts by way of fees. So not really an attempt to ‘lock’ in a future parliament. S 26(3)-(4) were repealed by the Higher Education Act 2004, which permitted variable (top-up) fees up to a cap.

I do enjoy a good bit of legal history, so thanks for that.

I think you could just have fairly dealt with the promised ‘tax lock’ by describing it as meaningless twaddle.

Whether it’s a promise to legislate not to do something or a promise not to do something, it’s just electioneering. I recall the Tories saying they had no plans to double VAT (a promise they kept as they ‘only’ increased it from 8% to 15%) and Labour promising not to introduce university ‘top up’ fees which they did introduce.

By the way, you are mentioned in dispatches on another tax campaigning website for your involvement with the Avaaz letter to HMRC about HSBC and the LDF. I don’t know the details so could you clarify? Is it just the HSBC/LDF ‘link’ that is being queried by Avaaz or the whole concept of the LDF?

Thanks Andrew. The fullest report is in the Guardian – which also prints the Letter Before Action which specifies full detail of the claim.