Every year HMRC publishes its estimate of the so-called Tax Gap.

What is it?

So the Tax Gap is predicated on Parliament’s intention in making the law. It measures (what HMRC considers to be) the difference between the tax Parliament intends should be collected and the tax HMRC actually collects. It doesn’t measure the tax that Parliament hasn’t asked HMRC to collect. So if Parliament doesn’t intend to levy, for example, a window tax the fact that there are no receipts from a window tax won’t make the Tax Gap bigger. If you wanted to measure the tax that might be collected if we had a window tax you’d first calculate the size of the Tax Gap – and then you’d add whatever yield a window tax might generate.

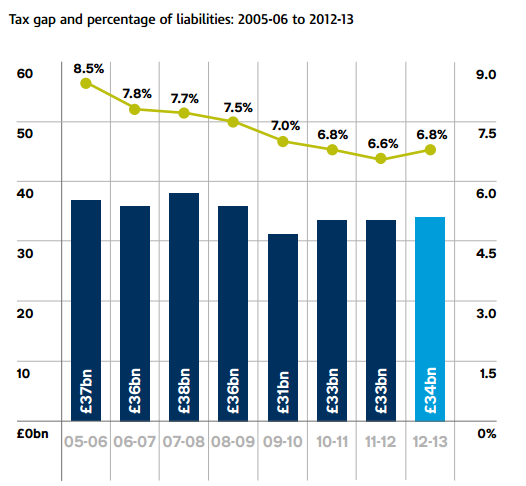

Another important thing to note about the Tax Gap is that it’s reasonably stable in both absolute and relative terms.

The latest estimate of the Tax Gap can be seen here. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: although it is inconvenient to Labour – I am a Labour Party member and it is inconvenient to me – the Coalition did a reasonable job of shrinking the Tax Gap.

And HMRC are generally thought to be doing a pretty good job in measuring it. Here’s the NAO late last month:

Of course, it’s theoretically possible that HMRC and the National Audit Office and the IMF are all wrong and the Tax Gap is massively understated. Possible, but unlikely.

I apologise for labouring these points. But they’re important because, along with £93bn of so-called Corporate Welfare – which I’ve addressed at some length here – closing the Tax Gap forms a central plank of so-called Corbynomics.

Here’s what Corbyn says about it:

So is there really £2,000 for every man, woman and child in the country in closing the Tax Gap?

No. Unambiguously no.

Here’s how you get to that conclusion in three easy steps.

(1) There’s no worldwide conspiracy involving HMRC, the NAO and the IMF to hoodwink us as to the size of the Tax Gap. The Coalition Government wasn’t party to such a conspiracy – and neither was the last Labour government before it. HMRC does a decent job in calculating the size of the Tax Gap.

(2) The reason the Tax Gap is where it is is because it’s extremely difficult to close. Every Government ever has come into office saying it will tackle avoidance and evasion – but still we have a Tax Gap which is reasonably stable in amount. There are only two explanations for this. Either every Government ever has deliberately chosen to leave the Tax Gap where it is. Or try though you might a certain amount of leakage is inevitable and all you can hope to do is narrow the gap a bit. Those are your choices – and only one of them is plausible.

(3) Some other number might measure some other thing. It might measure what Parliament could levy if it changed the law. And that other number might even measure that thing plausibly. But raising £2,000 for every man, woman and child involves identifying what that change in the law is – a new window tax for example – and identifying how much it will raise. The extract from Corbyn’s manifesto given above – purportedly supporting the £120bn yield – doesn’t identify any new tax. And Corbyn’s record on calculating yield is poor: I give an example here.

So what use, then, is the Tax Gap? Well, HMRC tell us:

The mundane truth, I’m afraid, is that it’s a sophisticated performance metric for HMRC. It measures how well they’re doing and where they should target their resources.

The Tax Gap is not a serious tool for making broader economic policy. It is no magical pot of gold that will obviate the need for close engagement with the choices inherent in being in government. And it’s not a basis upon which you can pitch to a sentient electorate. It just isn’t.

Follow me @jolyonmaugham.

Just a small point, but I do think the argument that a *progressive* tax system demands more attention to the tax gap is a bit shaky. One of the biggest differences between HMRC’s estimation of the tax gap and Richard’s is over the size of the shadow economy. The shadow economy is necessarily dominated by individuals and small traders. If Richard were asked whether the elimination of the tax gap as he identifies it would be progressive or regressive I don’t think it at all certain that he could answer that it would be progressive.

This touches on one of the more fundamental and constant issues in the debate on avoidance/evasion which is the ability of the commentator to select whatever biased position is convenient for the argument.

I have no doubt that the gap exists and no doubt that the best efforts of Governments of all colours will do little to move it significantly. I also recall however that value of that gap as measured by Mr Murphy has been comprehensively denied by HMRC which places it around 75% lower?

This is also noticeable in the recent decision in the Judicial Review of APN’s from Mrs Justice Simler DBE (www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2015/2293 ) where various “reasons” put forward by HMG that seek to justify the retrospective effect of the regime were accepted without critical review. Unfortunately I suspect that for so long as one side of the debate remains a “given” and not seriously challenged, achieving a clear picture is not going to be achieved.

Jolyon,

I echo these comments. In fact, not only could I could expand on them but I have already done so last summer! You may recall as you spoke at the event. It was at a meeting in the Commons on Tax Transparency, chaired by Margaret Hodge.

Click to access Tax-Transparency-Tax-Gap-discussion-paper.pdf

It concluded, like you, that “The key is that the Tax Gap must be viewed as a tool of HMRC’s trade and not as an entity in itself. Measuring it must be done on a consistent basis; trends must be sought and reacted to. In many ways the definition and how and to what extent avoidance (or whatever) is included doesn’t matter. Equally, the absolute number is arguably irrelevant – the only certainty we have about it is that it will be wrong. But it remains important to measure the gap and use it as one of a variety of tools to target resources and assess HMRC’s progress.”

One often under-reported part of the Tax Gap is that the estimate for avoidance is £3.1bn; that for the hidden economy and criminal attacks is £5.9 and £5.4bn. If the alternative figure for evasion is correct – £80bn – then how much untaxed activity can there be. Whatever the rate(s) involved (eg at 40% there is £200bn of untaxed activity), it also suggests our other data on things like employment and earnings need significant corresponding adjustments. After all, the fruits of that evasion must be going somewhere.

At the risk of boring your readers it might be instructive to highlight the IMF and NAO criticisms of HMRC’s methodology, and put them in context. To me they do not read as root and branch disavowals. But readers may simply stop here and stick with Jolyon’s view “And HMRC are generally thought to be doing a pretty good job in measuring it.”

The IMF began on p8 with

“In general, the models and methodologies used by HMRC to estimate the tax gap across taxes are sound and consistent with the general approaches used by other countries. The HMRC program follows a pattern of employing “bottom-up” based estimates for the direct tax gaps, and “top-down” estimates for the indirect tax gaps. Both approaches are applied consistently with good international practices—in fact, HMRC has been leading the application of some of these methodologies. Notwithstanding these good practices, there are areas of improvement that would enhance the robustness of the analyses. Sections II and III provide in-depth analyses of the models and methodologies used in measuring the tax gap, and provide some recommendations for improvement.

The IMF recommended future research (para 67) into “Three possible areas of research could help improve in the medium term the HMRC’s tax gap analysis program: (1) assessing possible top-down models for the income tax gaps; (2) extending the HMRC’s models to assess the size of the policy gap by tax type; (3) and comparing and contrasting the output of the FAD Revenue Administration Gap”.

On the top-down recommendation it is worth quoting in full what the IMF said:

“68. A top-down model at the very least would provide a useful means to verify the broad validity of bottom-up estimates, and also to estimate the policy gap. It is acknowledged that there are some serious modeling challenges and significant data issues to

be addressed in trying to develop a top-down model for direct taxes, as the HMRC has documented. (Rubin, Marcus, “The Practicality of a Top Down Approach to the Direct Tax Gap,” HMRC Working Paper No. 12, August 2011.) However, there are also some serious modeling and data issues inherent in any bottom-up estimate as well, so having the results from a top-down model to serve as a point of comparison, rather than as the primary means of estimation, could improve the overall analysis of the size and trends in the direct tax gaps. Of course, the cost of doing this

exercise will have to be assessed to appraise if these costs would outweigh the benefits.”

I cannot read these comments as anything more than possible refinements of the existing approach, certainly not a vote of non confidence – which would be entirely out of line with their opening views.

The NAO said, in addition to Jolyon’s quote:

“2.11 No measure of the tax gap can be definitive, and there will always be uncertainties inherent in such a calculation. HMRC must also balance the cost of refining its estimate with the added value such additional work would provide. We consider it useful that

HMRC has produced a measure of the tax gap as an indicator of the scale and nature of non-compliance with the tax rules, and as a broad indication of its performance over time. It is also a strength that HMRC publishes a comprehensive analysis of its tax gap estimates so that the basis and limitations of the measure are clear and understood. HMRC supplements the tax gap with more timely sources of intelligence about tax at risk to help it respond in an appropriate and timely way to known and emerging threats.”

Thanks Iain: a thoughtful, balanced and sophisticated contribution to the debate.

Great article, confirming what I had long suspected to be true. Do you know how the UK tax gap compares with other, similar economies?

The EU Commission did a survey of the VAT Gap across the EU and we are at the low end. I think there are other comparative studies too – but I can’t immediately think of by whom.

I’ve not got to hand the detailed sources but not many countries do a tax gap analysis. The UK does this more frequently but I doubt if each country has identical methodology. On the basis of those who do publish the UK compares quite well. In 2010/11 the UK’s net tax gap was 6.7% of its total tax liabilities; the USA’s tax gap is 14 per cent; in Sweden 10 per cent and in Mexico 23 per cent.

But the tax gap and ‘corporate welfare’ spend don’t form a central plank of Corbynomics – so this whole post is straw man stuff.

Not a single penny of expenditure is predicated on either the £120bn or £93bn figure …

Yep, those numbers – £120bn and £93bn – amounting to more than 41% of gross annual tax receipts are clearly given space in Corbyn’s manifesto for no reason at all.

But I’m pleased you don’t challenge the logic.

Pingback: Tax Research UK » What use the tax gap? A defence oif a key element in #Corbynomics

Well, according to Richard Murphy his measure of the Tax Gap is definitive. Because, well, he said so.

In your piece, you seem to accept the figures prepared by the HMRC without question and thus, conclude that the coalition has done a good job. Clearly, I am not in a good situation to estimate this but I have seen figures that show a failure to achieve forecast tax collections on most lines. These forecasts were compiled reflecting current policies on taxation. Your extract of the NAO conclusions excludes points 2.6 to 2.11.

Regarding accepting figures from an organisation who has been set this as a target to improve, I know how figures can magically turn from bad to surprisingly good when it’s likely to damage your bonus. Accepting figures from a source who is assessed on that target is niave. To deny any other estimate without examining the evidence, support and calculations shows blinkeredness.

I don’t think that’s quite fair. I say, in essence, that HMRC prepares figures, the NAO signs them off as pretty good and so does the IMF. Not perfect but pretty good.

You may have a problem with those figures. You may even be right to. But when we get to the meaningful question – can Labour sell to a sceptical electorate the idea of some conspiracy involving HMRC, the NAO and the IMF to understate the tax gap – the answer I think is (clearly) ‘no’. If that is the meaningful question then your personal view as to the accuracy of the figures is of academic interest, as is mine. And that’s why I set the argument out as I did.

Interested to see the figures showing variances in collection against forecasts.

I wonder if these are the Treasury forecasts of tax collection, as against amounts collected? I ask, because I don’t think HMRC does, or could, issue estimates of amounts to be collected as it is not a Ministry of Finance.

If so, they are not the same as the Tax Gap calculations, which try to measure shortfalls in specific areas.

I think any critique of Tax Gap methodology could not at the same time give you an estimate, or a more reliable estimate, of overall tax receipts ove say CSR 2015.

Pingback: Corbyn adds private-sector twist to ‘right to buy’ | World Money Grid

It’s hard to identify the differences between you and Richard Murphy (who seems to be the main target here), because you both put your arguments in such polemical terms. You seem to be arguing that the Tax Gap is and should only be a technical method for evaluating the effectiveness of HMRC as a bureaucratic arm of the state. I think Richard assumes that the Tax Gap is and should also be a policy tool, since identifying which social groups manage to avoid tax should help with tax design and as well as enforcement Surely he has a good point? Michael O’Connor may be right in saying that identifying the elements of the Gap does not necessarily mean that it is the wealthiest who are responsible for it, but that doesn’t negate the point that it can and should be a policy tool. You may be right also that the Gap might always remain more or less the same, but that doesn’t mean that tax design can’t be improved and result in improved revenues, as well as greater fairness/progressivity. As regards calculation of the Gap, you are perhaps right to point out that the IMF, and hence the NAO, overall approved HMRC’s methodology, at least compared to their peers. But Richard is surely correct in pointing out that they also said that HMRC’s methodology should be improved by adding top-down calculations, which is exactly what he advocated.

Hi Sol,

A privilege to have you commenting here.

But I’m not sure I’d accept your assessment. I haven’t (yet – I’m thinking about whether I want to) expressed any personal view on whether HMRC’s calculations are right. I’ve merely said that they are those of HMRC, which have been broadly approved by the NAO and the IMF. I (of course) accept that the IMF have suggested some improvements but it’s something of a leap to assume that effecting those improvements will lead to the Tax Gap getting bigger. And it seems to be inconsistent with their fundamental assessment (that HMRC has done a good job albeit that there’s scope for improvement) to imagine HMRC might be out by a factor of four. Ultimately, as I say to Pob in another comment, the question that’s of interest to me is: what evidence as to the size of the tax gap might persuade a sceptical electorate – and on that evidence there is only one possible answer.

But put that aside for a second. Assume (against HMRC, the NAO and IMF) for a second that £120bn is the right number. Is that number collectable?

To believe that there are huge revenues waiting to be collected – in other words that the tax gap is more than a KPI for HMRC and is an undeveloped and meaningful source of revenue – you have to swallow some pretty unlikely propositions. £120bn is about a fifth of all tax revenues. There is no political gain for any Government in just leaving that money lying there. It’s about what will be raised from the 40p rate and the 45p rate together in 2015/16. You have to believe that the Tories would rather leave that £120bn uncollected then cut the top rate of personal income tax to 20p. Respectfully, that defies plausibility. You also have to believe that the last Labour Government did this too: £120bn hugely exceeds gross per annum spending on the NHS in the last Labour Government; did Labour really choose just to leave that money lying on the ground?

I should also say that it’s not my argument that the Tax Gap is merely a KPI for HMRC – that’s what the Tax Gap document itself says (as the quotation I give from it makes clear). Although if you think, as I do, that some tax leakage is inevitable and that it’s the job of HMRC to minimise it, you reach the same conclusion independently of HMRC. I do, however, agree (and indeed say quite explicitly) that the Tax Gap calculation should (and does) help HMRC target its resources. Where you and I may part company is that (as I’ve already said) I think HMRC already use it for that purpose; why would they not?

Best,

Jolyon

Sol.

There is much in what you say that I, and I’m sure others, can agree or buildon via discussion.

But I think it’s a little disingenuous to suggest all Richard is concerned about is to use thre Tax Gap as a policy tool. Some background might help us understand why this issue seems to polarise views.

Richard has views, which he clearly holds strongly. He has used this issue to lambast HMRC collectively, at Board level, and in respect of named civil servants, to suggest HMRC is not up to the job and that the Gap is very much higher than reported. Indeed, at times he has accused them of deliberately misleading the public. He does not seem to accept the NAO and IMF approved the HMRC methodology and treats their suggestions for improvements, as you correctly describe them, as damning criticisms. He states that his methodology and numbers derived from it are more robust and accurate than HMRC’s.

In such a climate it is perhaps understandable why there seem to be a lot of flashes of lightning but not much illumination or mutual understanding. It would be extremely welcome if someone or some body could do some research on this, preferably someone with no known connections to any existing viewpoints. Maybe a good PhD somewhere?

I think you’ll find that your comments on the use of the Tax Gap are exactly what HMRC says it uses it for. It’s there to ensure that resources are put against the areas where tax gaps are either growing or might be tackled cost effectively (including process changes and tax redesign). These gaps are not really to do with social groups but are cut in three broad ways: regimes, behaviours, and customers. I don’t think there is any analysis that links the three together.

There is also the issue that some groups have dismissed the Tax Gap and just told HMRC to collect the tax due from everyone, rich or poor. I think the TSC and Lords said something to this effect. And of course there remains the basic obligation on HMRC to do that, so I don’t think they have the luxury of throwing lots of resources at all the areas.

Of course, if Osborne gave them more resources, or at least exempted them from the 25/40% cuts, they would have more to do more. Its not always about boots on the ground but its also not always about better data analytics.

What I tried to argue was that Richard’s perspective raises issues of tax policy and not just the effectiveness of enforcement. That is because the two are inevitably related. You cannot take the law as a given, and measure only how effectively bureaucrats enforce it. How should we measure the effectiveness of traffic police in enforcing speed limits? A key aspect of the Tax Gap is that it helps to identify possible additional sources of revenue which would not need new taxes but better tax design and enforcement. The question is not whether you could collect that particular £120b, but whether significantly more could be collected by improved design and better targeted enforcement. I would have thought that most people would agree that reducing the scope for avoiding and evading tax improves the tax system and must improve revenues, though by how much is hard to calculate. Even on your view that the Gap is only a KPI, allowing HMRC to set its own performance indicator does not seem a good idea. The IMF and the NAO are hardly likely to lambast HMRC, and I’m surprised that you won’t agree that in suggesting that a top-down method should be added, they in effect accepted Richard’s argument. Richard makes his arguments forcefully, which does not make him popular, but he has been extremely effective. In this kind of company I find myself retreating into academic mode, arguing for a more balanced evaluation, though in academic contexts I’m generally considered forceful and opinionated.

I absolutely agree that we should always be thinking about better enforcement and design. Pretty much alone amongst practitioners in the UK I have spoken out in support of measures Labour and the Coalition took to improve collection. I’ve also, myself, suggested a number more which have found their way on to the statute books. So that, I agree, is a sensible conversation to have.

Sol,

Thanks for this additional comment.

Of course HMRC is not responsible for tax policy, although it has discretion on the allocation of resources and its operational approach to enforcement and compliance. It’s bit like shooting the messenger for HMRC to get the flak for the outcomes of Government tax policies.

But I think your position is closer to HMRC’s than might be apparent. Regardless of debates on the size of the Gap, HMRC already makes use of that information to help reach those resourcing decisions. I’m sure they also feature in discussion in the Treasury on tax policies. And judging by the its recent stakeholder event HMRC also seems to agree about improved design and better targeted enforcement, hence the Promote, Prevent, Respond compliance strategy.

I do not see the Tax Gap as any measure of KPI (e.g. no commitments to reduce it by so much by a certain date). I think it is more of a long-term strategic aim, especially as there are factors that are not under HMRC’s direct control (eg a resurgence in tobacco smuggling or MTIC fraud caused by changes in the tax rates of another country).

On the specifics of the Top Down approach the IMF recommended research into it. As I previously quoted they accepted “some serious modelling challenges and significant data issues to be addressed. ” HMRC thinks these are too big to resolve. Are they right? It would be an area where academic research can help assess problems and identify possible solutions – another good PhD?

Finally, I think Jolyon’s reply is a little unfair to the profession. I’m sure others (including public sector unions) have supported efforts to combat avoidance and evasion, see, for example, “The coalition government has harnessed the tide of anti-tax avoidance sentiment to introduce a raft of legislative measures designed to cut off the source of avoidance schemes, to get rid of cash flow advantages for participators in such schemes and, through the GAAR, to make it pointless to enter into aggressive tax avoidance. At the same time, the government has been in the forefront of international efforts to deal with multinationals’ profit shifting and has put extra resources into tracking down and flushing out tax evaders. All in all, the coalition government has done what it said it would do.”

http://www.taxjournal.com/tj/articles/tackling-avoidance-coalition-s-end-term-report-30042015

I’m not sure your criticism of my “pretty much alone amongst practitioners” is substantiated by pointing to public sector unions. It is especially difficult for someone working in the field for taxpayers to argue often against (in effect) his clients’ interests. I’m sorry you are not prepared to recognise that.

Jolyon,

I just said I thought it was a little unfair and also quoted an article that seemed to line up with your views.

I can certainly recognise the tensions you describe. But I doubt if public sector unions endorsing your position would help you either!

But if I’m wrong then glad to speak up in favour.

Well, I’ve made my point. You can either acknowledge it or not. For third party reader(s) (the ‘s’ may be optimistic) I’ve written about my personal position here http://wp.me/p3D1eN-rI

Pingback: The Tax Gap (Redux) | Waiting for Godot

Pingback: Tax Research UK » Is there a £100 billion hole in Corbynomics?

Pingback: Corbynomics and the magic money trees | Richard Angell