The following is my contribution to last night’s ICAEW Wyman Symposium.

I am a Queen’s Counsel. You would, therefore, be surprised were I to begin otherwise than with some flamboyant – and on analysis rather tenuous – display of my qualities as Renaissance Man. And not merely surprised. You would leave this evening with that most acute of disappointments: the disappointment of an unmet expectation.

Fear you not.

I take my theme tonight from Orwell’s ‘Keep the Aspidistra Flying’. “There are,” he wrote:

“so many pairs of lovers in London with ‘nowhere to go’: only the streets and the parks, where there is no privacy and it is always cold. It is not easy to make love in a cold climate when you have no money.”

That in a sense is the background against which we all speak before you today: how HMRC should collect tax in a cold fiscal climate.

Some statistics.

In 2005 HMRC had 96,000 FTE staff. By July of last year this had fallen below 60,000.

In 2005-06 the outturn sum spent on HMRC Administration was £3.7bn. In the Annual Report and Accounts for 2013-14 it was expected that £3.1bn would be spent. The cut in real terms will have been larger still. On 4 June 2015 the Chancellor announced a further £80m cut – with more in store.

As a profession we might – indeed we do – complain about this. I could join in that chorus. But the ICAEW has not invited me here to make political points. Nancy Mitford took that line ‘love in a cold climate’ as the title for a novel. In that novel she wrote:

“The worst of being a Communist is the parties you may go to are – well – awfully funny and touching but not very gay… Left-wing people are always sad because they mind dreadfully about their causes, and the causes are always going so badly.”

Let me take her message to heart. I will not ruin the esprit of the evening by minding dreadfully about the cause of better resourcing for HMRC. And let me urge you, too, to eschew that course – at least for the next five minutes. Let me invite you, instead, to consider how HMRC should exercise its powers of care and management in a cold fiscal climate.

You have heard vigorous complaint of legislative measures adopted by successive Governments to tackle avoidance DOTAS, the GAAR, APNs, FNs, POTAS and so on. Let me give you some data. Direct Tax DOTAS disclosures fell from 503 in the first financial year of DOTAS to fewer than 10 in the six months ending September 2014. VAT disclosures fell from 680 to fewer than 5 in the same period.

In a cold fiscal climate these legislative measures have helped stop (disclosable) tax avoidance. “Helped,” because the courts, too, have put their shoulders to the wheel. As I rather shyly put it elsewhere, judges hearing avoidance cases in recent times have “occasionally articulated their instinct to fairness against the grain of the legislation.”

That decline in DOTAS disclosures largely pre-dated the changes in the Finance Act 2014 that so fundamentally altered the economics of tax planning going forward. But those Finance Act measures enabled the collection of a projected £7bn of tax avoidance fruits.

If it is to be said that we might have tackled tax avoidance – and enabled the collection of these enormous sums of money – without those measures and with lower levels of resource then I’d like to hear ‘how’. Because the public, to whom politicians are accountable, have demanded action, and the Coalition Government, on avoidance at least, delivered substantial advances. How else might they have been delivered? Sensible public accountability is much of what a Government exists to provide.

I have touched on avoidance but the challenge going forward will lie in tackling evasion. If you add together in the Tax Gap figures those for criminality, evasion and the shadow economy you get north of £15bn. And the Coalition Government announced shortly before the election that it would consult on and introduce a number of measures to close that gap.

Those measures will include, in particular, a strict liability offence for offshore tax evasion. We have yet to see the detail of that offence but (subject to two provisos) it is something I think we should support. I would like to see a de minimis threshold and a defence of taking advice from an appropriately qualified advisor.

Experiences such as the failed Harry Redknapp prosecution have left HMRC scarred – and institutionally disinclined to prosecute complex tax evasion. It is clearly not in the public interest that there should be effective impunity for well-resourced defendants.

There has been a lot of debate around whether HMRC should target a more vigorous criminal prosecutions policy. HMRC’s job, it is said, is to maximise yield and not to bring prosecutions.

I regard, I have to say, that argument as wrong-headed for a number of reasons.

The argument that chasing criminal prosecutions jeopardises yield draws on the fact that the threat of criminal prosecution will dissuade today’s evaders from coming forward. There is something to that. But what it ignores is that delivering immunity from prosecution to today’s evaders sends a counter-productive signal to today’s compliant taxpayers. “Why should I pay,” they may well ask, “when my neighbour who doesn’t pay suffers no sanction.” The argument for generous amnesties seeks to solve today’s problem – at the price of creating a new one for tomorrow. It just kicks the can down the road.

It is also misleading to say it is HMRC’s job to maximise yield. HMRC’s job is to provide careful stewardship of the tax system. There is no legal authority for the proposition that HMRC would be acting inappropriately if it chose to prioritise criminal prosecutions to encourage future compliance. And – and here I do draw myself up to my full Silken height – there is no conceivable world in which a Judge might criticise HMRC for taking that step.

Finally, of course, there is room for guarded optimism that the world is changing to improve HMRC’s sightlines between tax evaders and their undeclared income. The Common Reporting Standard will further undermine the argument that the UK has no choice but to offer sweetheart deals to tax evaders otherwise we’d never get any of their unpaid taxes. That argument has always struck me as confused: if we really have no prospect of catching the evaders then what could an amnesty deliver? Why would they volunteer?

So I say a combination of better sightlines and meaningful sanctions – a strict liability offence – may restore dignity to civil servants given the difficult job of defending flawed policy choices made by their predecessors. That combination will provide an impetus to disclose.

A few short observations to finish.

First, advocates are inclined to focus on high legal principles. We like to deal in absolutes. But let me tell you a secret. Our sources of constitutional law are alive. Our Judges use them to help mediate between the competing demands of the contemporary body politic and that which we say we hold sacred. But Judges will always interrogate for signs of common sense an advocate’s appeals to that which she says is sacred. And when you make up your minds about what you’ve heard tonight so should you.

Second, I sound a note to judges. Collecting tax in a cold fiscal climate requires an expansion of HMRC powers – that’s been my theme for the evening. But as more executive power flows to HMRC the demands on Tax Judges to moderate that power grow too. Personally, I’d like a strong sense of that from the specialist judiciary.

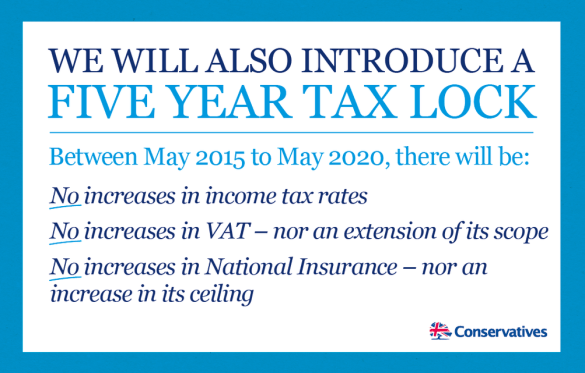

Third, resources. I promised I wasn’t going to spoil the party by “minding dreadfully about my causes” but there are problems that legislation can’t solve. How will we legislate to stop tobacco smuggling, which costs £1.6bn per annum? The Conservatives promised to bring in a further £5bn from tax avoidance and evasion. Few in this room would advise any client of yours who had ambitious revenue targets to begin by cutting the sales force.

Finally, HMRC. It is critical that the Department maintain or recover something that many people in this room will think has been lost. We will all readily be able to conjure examples of HMRC taking points that it shouldn’t. This stems, in my opinion, from an incipient culture taking hold that HMRC’s job is indiscriminately to maximise revenues. That is fundamentally to misapprehend its job. Whenever HMRC issues an Extra Statutory Concession it recognises that there is some equity in tax. Reigning back that culture is a matter of departmental leadership. I do hope we will now see that leadership.

You must be logged in to post a comment.