We talk a lot about taxing the rich – and perhaps we should. The rich become rich by operating in a system that the state enables. And the contention that taxation amounts to a deprivation of their money

is internally inconsistent. The rules of the game at which the rich win include a price to play. I cannot opt to abide by the rules that benefit me – but not the rules that don’t. No one forces me to accept the offer of my neighbour on the left to give him half the plums I collect from his tree. But if I do the half he gets were never my plums.

But this ineluctable logic can’t be pushed too far. Not if my neighbour on the right also has a plum tree – and he’ll let me keep 60% of the plums I harvest. Not if I decide that if I only get to keep half it’s not worth collecting the plums at all. And not if I took the view that, if I vault the fence in the dead of night, I might get to keep all the plums.

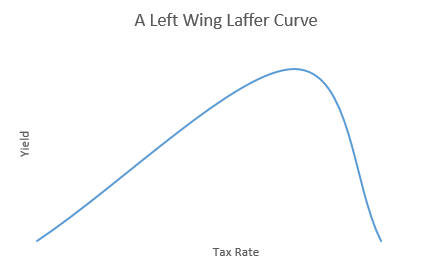

These ideas – and others – are all expressed in a relationship we call the Laffer Curve. We call it that wrongly, and uselessly too. Wrongly, because there is no one Laffer Curve. And uselessly, because no one knows what it looks like.

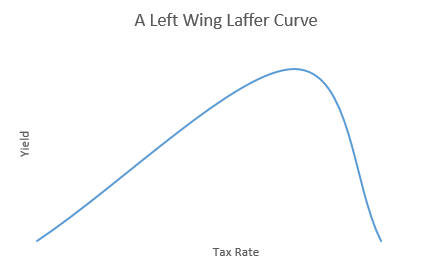

Here’s a Laffer Curve for income tax.

What it shows is (1) that if you have a tax rate of zero, you don’t yield anything. Few would argue with that. And (2) if you have a tax rate of 100% you also don’t yield anything because no one works and so no one pays tax. That’s slightly more tendentious: there’s always someone who so loves his job that he would carry on even if everything he earned went to the state. But let’s press on with the argument – leave Tax QCs to one side for the moment – and assume that at tax rates of 100% no one would work.

The logical consequence of these two propositions is that there is a rate more than 0% and less than 100% at which the tax yield is the highest – what we call the ‘revenue maximising’ point. Set tax rates too low and Government relinquishes more plums than it must. Set it too high and your taxpayers may defect to your neighbour, not bother at all, or be heavily incentivised to find ways to dodge your plum tax.

This is a basic – but incredibly important – insight.

It explains why there is a point beyond which raising taxes is counter-productive (in revenue raising terms anyway) for Government. It explains why, if the aggregate earnings of everyone in the country is 100 taxing them at 20% might raise 19 but taxing them at 80% won’t raise 76. It explains how Ed Miliband’s Labour could argue that cutting income tax from 50% to 45% was a £3 billion tax cut for the wealthiest; the Coalition could respond that it would only cost £100m; and (on the best available evidence) they could both be right.

It’s also a useless insight. Of course, if your neighbour could work at what this rate was he could maximise the amount of plums he got to keep.

But he can’t. Tax theoreticians on the right argue a Laffer curve looks like this.

They argue that high tax rates disincentivise work, stimulate emigration and generate tax avoidance. And they’re right. They also argue that tax rates reduce economic growth – reducing the number of plums on the tree (loosely speaking). And they argue that the consequence is that the yield maximising rate is a low one.

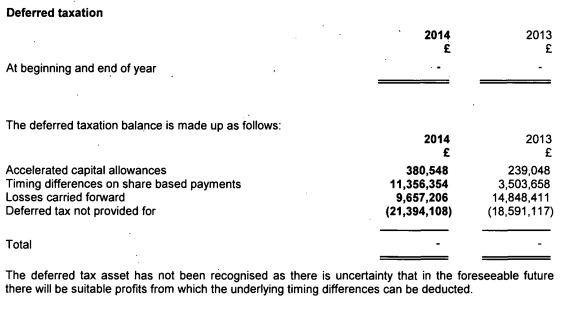

Those on the left argue for one that looks like this.

They agree high tax rates can disincentivise work, cause emigration and tax avoidance. But they argue these effects are overstated and that higher tax rates need not stunt growth. You can push tax rates much higher, they say. And they argue that those who can afford to pay more tax should do.

But this debate rarely rises above assertion and counter-assertion. Because what we know about the shape of the curve is precisely nothing.

We know that today, with our top rate of tax at 45% on income above £150,000, the 332,000 who earn above £150,000 will pay about £49.1bn in income tax in 2015-16 (Table 2.5 (2015-16)). But we don’t know what the world would have looked like today if, for example, Government hadn’t decided to raise our top rate from 40% in 2010-11.

Would there be more (or even fewer) than 332,000 people with income of above £150,000 paying income tax in the UK? Would they be earning more or less in aggregate that they do now? Would they have engaged in more or less tax avoidance? Has a 45% rate had a negative impact on economic growth – or more accurately earnings growth – or more accurately still earnings growth amongst very high earners? What are the effects of that increase on those earning below £150,000? We can speculate on any one of these effects. But unless we can speculate accurately about all of them – and we can’t – we can’t answer the question whether Government receives more in income tax now than had it stuck with a 40% rate.

We can’t construct a sensible counter-factual for the world as it might have been. And nor can we construct a sensible counterfactual for the world as it might be if we were to change rates tomorrow. But from the discourse on the left and right you’d be forgiven for thinking we could.

Here the left’s spokesman du jour Jeremy Corbyn:

Fair taxes for all – let the broadest shoulders bear the biggest burden to balance the books.

He might be right that the broadest shoulders should bear the biggest burden (and in a sense they already do: the highest earning 5,000 taxpayers pay a total of £9.43bn in income tax, or more than 5.5% of all income tax receipts). But it’s a non-sequitur to assert that raising taxes will balance the books, indeed if you tip into the downward slope of the curve you’ll further unbalance them.

And it bedevils much thinking on the right too – here’s Nigel Lawson talking of cutting the top rate to 40%:

I would strongly support this: It would significantly enhance the attractiveness of the UK as a place to do business, at no cost in terms of lost revenue.

That was the experience when I brought the top rate down to 40 per cent in 1988 and it is even more relevant today.

The (let us assume) fact that cutting the tax rate from 60% to 40% was revenue neutral absolutely does not have as its consequence that further tax cuts would be revenue neutral too. (You can test this hypothesis by looking on any Laffer Curve of the effects on yield of cutting tax rates from 20% to 0%).

The IFS’ pre-election estimate of the exchequer effects of raising the top rate from 45% to 50% doesn’t quite fall into this trap:

But it’s important to recognise that HMRC’s estimate from March 2012 (a document that still makes – if you’re of a certain mindset, anyway – for interesting reading) will be of very modest value now. The shape of the curve is affected by a variety of externalities that change over time. The marked success of the Coalition in tackling tax avoidance will reduce what I’ve referred to as dead-of-night fence-vaulting. Put shortly, it will have shifted the revenue maximising point to the right. So too, and markedly, will restrictions in pension tax relief for high earners. But the Coalition also adopted other tax measures which will have shifted the point to the left. And that’s before we move on to effects external to the UK.

I stress these points because they’re what I find most interesting. The political potency of the inequality narrative won’t diminish any time soon. And so the question whether to change income tax rates will continue to find its answer in political rather than fiscal considerations. Nigel Lawson knows this, of course. As (one imagines) do Corbyn’s advisers. Both are embarked on what virtue signalling looks to their respective supporter bases. But it’s no more than assertion: stay sentient folks.

But, as I sought to stress back when I was involved in Labour’s tax policy making, alongside the virtue signalling it’s worth considering how to maximise the yield from changing tax rates. This is a truth that applies to both upward and downward rate change – but I don’t get much sense that many policy makers think like this. Although we can’t know what a Laffer Curve looks like we can still seek to shape it in advance of rate changes. And that’s as universal a truth as you’re likely to find in tax rate policy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.