It’s a curious paradox that the delivery of the Conservatives’ desire for a smaller state, a desire born of a belief in the inefficiency of that state, throws up inefficiencies all of its own.

How we laughed at the logic that led us to consider underwriting private sector investment in the nuclear power industry at a cost exceeding that which would be incurred were we to borrow and invest ourselves.

And cried, at the Chancellor’s attempts to wrest from the tax system – one that already exempts the lower earning half of the adult population from liability to income tax – some meaningful amelioration of the swingeing cuts to tax credits that hit hardest that same half.

My own particular cranny of expertise is, of course, neither off-balance sheet financing nor how best to balance the moral imperative to tackle poverty against the desire to run a balanced budget and properly incentivise work. What I know about is the uses that our politicians make of our tax system.

But here too we find inefficiencies – borne of the same desire. And which will have profound consequences for the outcome of the Comprehensive Spending Review.

***

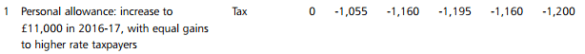

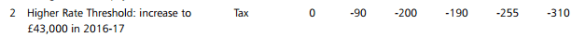

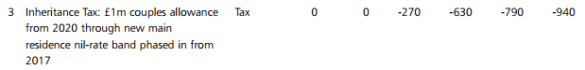

Decisions around the rates at which we pay tax – cutting corporation tax to 18% or the top rate of income tax to 45% – are closely scrutinised. So, too, are decisions around thresholds: raising personal allowances to £12.500, or the point at which you pay higher rate tax to £50,000, or the threshold before a couple must pay Inheritance Tax to £1m. For changes of this type, it is relatively straightforward to identify the cost, the beneficiaries, and the advantages.

But alongside these headline decisions sits a host of further choices made by Government to favour certain types of business activity, or individual, or activity.

This favouriting usually takes the form of a reduction in liability to tax – and sometimes payments made to the chosen subject by HMRC. But from our perspective of course – the ‘our’ here being you and me: society at large – the form makes no difference. Either we incur expenditure by handing over cash or we forego cash by choosing not to collect that which would otherwise be our due.

The technical term for these encouragements is “tax expenditures” – reflecting that through them Government is foregoing or ‘expending’ tax that might otherwise be collected. But unlike the headline decisions around rates and thresholds, the scrutiny of tax expenditures is unsatisfactory – and the evidence of their efficiency weak.

But before I get into how they’re unsatisfactory and weak let me tell you why this matters.

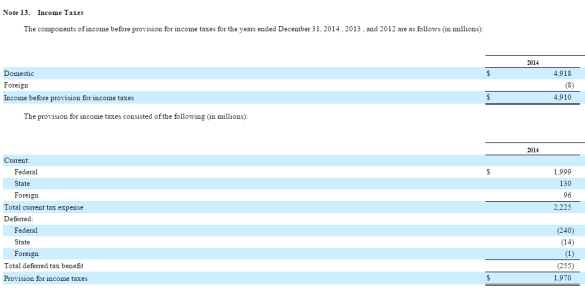

We’re talking staggering sums of money here. An Office for Tax Simplification report identified the existence of over 1,000 reliefs. The 50 tax expenditure reliefs which find their way onto the (somewhat misnamed) “principal” tax expenditure spreadsheet – these 50 alone – cost us collectively £111bn in 2014/15. That’s about 20% of all the tax of all types we collected that year.

Now that I’ve piqued your interest let me explain how it’s weak and unsatisfactory.

First, what the electorate is told about the purpose of these tax expenditures is often a stranger to the reality of what they actually accomplish. Last week, for example, I wrote about the so-called Shares for Rights scheme. It was heralded by Government as a mechanic to create partnerships between workers and owners of businesses. But the reality was it was little more than a £1bn bung to wealthy private equity buyers. And it appears to have been designed as such.

Second, how the benefits are shared is poorly understood. Richard Murphy has given the example here of how entrepreneur’s relief (which cost a total of £2.77bn in 2013/14) delivered a tax saving of a staggering £600,000 (on average) to each of 3,000 people. True it is that Richard was able to effect that calculation from publicly available information – but the same is not true of most tax expenditures.

Third, their costs – in tax revenues foregone – lack transparency. HMRC publishes three spreadsheets showing the costs attached to tax expenditures. The first – here – sets out what are described (somewhat misleadingly) as the costs of the “principal” tax expenditures. The third – here – describes the costs of “minor” tax expenditure reliefs (i.e. below £50m). But (and this is why I describe the title to the first as misleading) there is also a second – here – with the title of “cost not known”. And that second includes some punchy items – like the £1bn+ cost of Shares for Rights – which should quite clearly come within the first, “principal” tax expenditures, spreadsheet.

And it’s not easy to avoid the conclusion that that lack of transparency is sometimes deliberate. Let me give some examples:

- The Shares for Rights scheme appears on the “cost not known” spreadsheet – despite the fact that Treasury promised at the time to monitor it. Moreover, as I pointed out in my post last week, the OBR was perfectly well able to estimate the £1bn+ cost. So you might be forgiven for some scepticism about the assertion that Treasury and HMRC are unable to.

- The second item on the “cost not known” spreadsheet is ‘10% wear and tear allowance.’ But how can that cost not have been known when, in July’s Summer Budget, the Government abolished the allowance, a measure that Treasury was able to estimate carried a forecast yield of £205m in 2017/18 (with more to follow in succeeding years)?

- The National Audit Office has made similar (and related) points in relation to Lettings Relief:

But a number of the items on the first spreadsheet – misleadingly marked “principal” tax expenditures – are marked as “particularly tentative and subject to a wide margin of error.” What’s the rationale for including them but excluding lettings relief?

It is temping indeed to conclude that the “costs not known” spreadsheet might better be entitled “costs we’re not going to tell you.”

And even where the costs of tax expenditures are published there are profound doubts about the reliability of those numbers. As the NAO pointed out:

(and that’s four of only ten reliefs the NAO examined).

And, critically too, fourth, there is no ongoing assessment of whether those reliefs deliver value for money. Even if you make the generous assumption in favour of the Government of the Day that the reliefs do deliver its assessment of value for money at the time they’re introduced, the structure of that relief, its cost and what it delivers, is not routinely reviewed to take account of changes in the economic climate.

Take Agricultural Property Relief from Inheritance Tax, for example. It is expected to cost us £420m in 2014/15 but what value does it now deliver? When I looked at that question here I concluded that whatever had been its original intention, it now acted as a barrier rather than a spur to the productive use of agricultural property.

Or Entrepreneurs’ Relief (which I have already referred to). The National Audit Office has calculated that the actual cost is fully three times what was forecast.

but there is no suggestion that this heightened level of expenditure is necessary to deliver the purpose of “encouraging enterprise”. Or even that Government has seen fit, in light of this much higher level of expenditure than anticipated, even to ask itself the question whether we get value for money from that 300% increase in the originally anticipated cost.

To take another example, a detailed literature review of the effectiveness of tax expenditures on research and development (at a cost in 2014/15 of £1.7bn) presented a very mixed picture. Certainly those reliefs became less effective over time. And we also did not know how effective they were to start with:

I could go on. But you have the point. For further reading I recommend this Report from the National Audit Office and this one from the Public Accounts Committee.

Given the scale of tax expenditure – over £110bn on 50 tax expenditures alone (HMRC estimate there are may be 150 in total) – these problems of disinformation, poor knowledge of costs and distributional effects, limited understanding of value for money and a lack of monitoring are profoundly troubling.

So Corbyn has been right to highlight it, albeit that his particular focus on corporate reliefs is difficult to understand.

****

But these issues rise above the party political: they ought to be absolutely centre-stage for all of us who care about efficient and well-run Government.

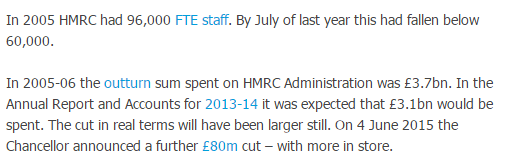

We have been told to expect £20bn of savings in the Government Spending Review, the results of which will be announced with the Autumn Statement on 25 November.

And, as has been well flagged, delivery of this £20bn number whilst meeting the pledge to ‘protect’ substantial parts of public spending, will involve swingeing cuts to some unprotected departments. Departments have been asked to identify prospective cuts of 25% and 40% – here’s one possible scenario the IFS has modeled:

And these cuts follow, of course, from substantial cuts achieved during the last Parliament.

No one would argue that the Conservatives – initially with the Liberal Democrats and now alone – have failed to look long and hard at how to cut expenditure. But where is the similar detailed focus on revenues foregone?

Because, of course, there is another way to achieve your goal of balancing the budget: you can increase your income. Or do a little of both.

It seems bizarre that you might look to balance the books solely through the mechanic of cutting £20bn of expenditure whilst turning a blind eye to the value for money delivered by your choices to forego income. Especially when there is a tidal wave of evidence that our understanding of that value for money is poor and the sums – in excess of £110bn for fifty tax expenditures alone – are so enormous.

Why would you choose to balance the books with one eye shut?

In another context Government rejected this analogy between revenues foregone and expenditure incurred.

And this rejection stands, apparently, despite the fact that these tax expenditures can and do take the form of cash payments made by HMRC to beneficiaries.

But whatever the merits of this reasoning – and I personally struggle to identify any – it is surely a truism to say that one can balance the books as easily by increasing your income as cutting your expenditure.

And you would only close your eyes to this truth if you were bent on shrinking the size of the state.

You must be logged in to post a comment.